Indisputable proof of God is not exactly what men—(rashness often being inherent of this demand)—would conceive it to be. The level of proof, after-all, which such spiritually-incredulous men are typically asking for, and refuse to be satisfied without, would be such that should have sufficiently rendered there being no need whatever to ever have debated the existence and reality of God in the first place; in other words, these impugning persons contradictingly make demand for proof to be supplied, of an extrinsic degree so obvious and so evident, that should have nullified their very need to have demanded any proof to begin with; for, those responding, as they seem to imagine, should have, at most, merely to point, and the question should at once be resolved by the questioner's directed observance of God's physical presence occupying a visible place in our world.

But of course, this type of manifestation is not the case with our Creator, for even deeper reasons than we shall take the time to relate below. Hence, the reality of God may be better understood by first understanding the power of doubt: For instance, an atheist might argue, "If God were to appear in the sky and announce Himself as God, to our world, in an overwhelming show of great thundering and earthquake, I would certainly believe that He existed. For how could I not? Not to believe, under these circumstances, would just be foolish!" And men may look upon this idea as the most definite, sensible, and most fair course of action for God—were He in fact real—to have simply undertaken from the beginning of time.

But should that same unbeliever, seeing such a manifestation, as he professes himself to require, appearing out of nowhere in the sky, and consequently being overwhelmed by the power and volume of what his ears absolutely assure him must be the very voice of God, emanating from what his eyes absolutely convince him must be the very image of God Himself,—should that witness suddenly be informed by some respected, government official standing beside him, that this grand, celestial spectacle at which he gazes is but the clever contrivance of a hostile alien species, who, having meticulously studied our ancient beliefs, in effort to appropriate for their psychological warfare that one Belief to which Man has shown himself the most susceptible, and then use that religious imagery by means of their advanced technology to enslave us and attain dominion of our world—well, this skeptic of a spectator would suddenly have great cause for doubt, and is liable to feel, in what he formerly took for the incontrovertible appearance of God, a suddenly grossly-inadequate amount of proof for that Spiritual Being's existence.

Moreover, such distrustful men, in gazing upon this overwhelming heavenly spectacle, and hearing that same Image profess Himself to be Sovereign God, may still, and indeed most probably will, inwardly persist in doubting the veracity of His claims, vainly wondering whether or not that God truly existed for all time, or has Himself a creator superior to Him, or whether or not He dwells in some other dimension among other gods equal to Him, and many other such unsubstantiated ideas, any one of which, nevermind their improvableness, will still seem to their unreasoning perspectives "within the infinite realm of possibility."

In truth, what matters is hardly any number of those questions (however profound in their scope some may appear) raised by such doubters, than it is the underlying reason for the doubt which perseveres in them. For, men do not so much doubt as a result of their questions, which are often seized upon as their defense in a reactionary instant, as they endeavor to use their questions to validate the willful doubt which they stubbornly refuse to relent of. The fact of the matter, is that Man invariably doubts what he disagrees with; what he, in the initial trespass of his pride, seeks still further to oppose (Amos 3:3); and, as ignorance is the ideal breeding ground for disagreement, particularly among such persons as are by nature already disagreeably inclined, a proper knowledge of God, Who's Characteristics are indisputably good, and commensurate with all of reality, is necessary to be perseveringly shared and communicated in order that men, for their own sakes, might be brought into agreement with Him.

What we find then is that no proof can be sufficient to the doubter by some external revelation. The revelation must be inward. Contrary to what we have been told, seeing is, in fact, no surety of believing. After-all, the Israelites saw many a miraculous feat of God's; and that sinful Doubt, as to His incontrovertible Supremacy, as to Him actually being God, still persisted and prevailed in their hearts. Moreover, we know many men to have struggled with a doubt of their reliable senses, on account of their nevertheless fallible nature. And as doubt—(an inward operation of man's will)—is therefore sufficient to topple the vivid experience of the eyes and ears, only an equally opposite operation on that same subjective plain, of that same inner will can alone be sufficient to counteract it's denying influence; that operation, of course, being faith, or trust.

Now, faith is no foreign concept to man's general experience with life, but is an essential catalyst to his getting along successfully in it. And faith is never acted upon apart from reason, but is in fact the culmination of all reasoning endeavors; is the crowning achievement of reason, so to speak; the highest pinnacle to which reason brings a man, before that man must inevitably jump, as it were, into the future-moment's uncertain and insubstantial air, if he would wish to progress any further. In a word, enduring faith is always firmly founded upon a bedrock of reason (John 3:21; John 18:37).

Take, for example, the simple act of boarding a plane: you have in your mind an understanding that planes have fallen from the sky and have crashed, but know this to be a rare tragedy, one very unlikely; though the consequence of such a catastrophe is of so serious a degree as to in all conceivable probability claim your very life, and with no little degree of terror. However, you hear of people and friends taking many flights, and hardly anyone ever seems to be concerned; and you personally know very few persons, if no single person at all, to have died in this manner. Thus, on the basis of these reasons you feel quite prepared to travel by this means; yet, in doing so, you are given no occasion to meet the pilot; in spite of all his required qualifications, you are never given any opportunity for yourself to observe, first-hand, what emotional, mental, or physical state that man enters the cockpit in, prior to your placing no less than your very life in his hands; neither do you feel the need to, in spite of having even heard of pilots flying drunk before, though such incidences be exceedingly rare. Much the same, you have known, heard, or read of plenty of incidences where qualified men have conducted themselves so irresponsibly with the numerous lives entrusted to them along with their own; and yet, knowing all of this, as well as being endowed with an intimate and innate understanding of man's outrageous foolishness from having observed it, however infrequently, flaring up in your own being, you nevertheless go ahead and take your chances, ultimately gambling with your life, much as you far more frequently do whenever riding as a passenger in a car or bus. And why do you make this decision? Because, you have faith in the airline, in the plane itself, and in the pilots; in other words, you have faith in the human engineers, in the vehicle, and in the human driver; and that, after-all, not unreasonably, though any and all of these functionaries may fail you, and have indeed failed at one period or another as cautionary history records; to put it simply, you have a faith in the aptitude of mankind as an overseer in your life. Or where else do we get the illustrious phrase, "My faith in humanity has been restored"?—though the very wording of this popular statement, (which has been said or thought innumerable times by men, and certainly at least once, by us all), betrays how undeserving of our faith mankind most certainly is.

Indeed, whether we know it to be or not, our moment-to-moment, day-to-day activity constantly testifies as to faith being an indispensable component to one's life; and that to go about attempting to resist any and all acts of faith, (the most misplaced of which must nevertheless be founded upon some degree of reason), proceeding therefore to question every little and trifling thing in life prior to entrusting yourself to its care,—(distrustfully doubting everything, for sensibly not knowing exactly what the future holds, because you sensibly know that it may in all possibility hold tragedy)—that an attempt of this kind and degree would not only be an impossible effort to accomplish, being contrary to even the most cynical man’s nature, but an effort which, by its very endeavor to exclude any and all faith in favor of pure reason, must become in the end the very opposite of reason itself, rendering one, plainly to the eyes of all others, an unreasonable, and fully reasonless person, as we unscrupulously judge such persons to be, whom live under a fearful or distrustful oppression of the unknown, and so exist in a state of nearly utter faithlessness.

Studying the nature of God—(that is reading and heeding His Word),—meditating on His character, one will slowly begin to reason things out in accordance with what God says of Himself, if that man fairly analyzes God's position as well as his own. Ultimately, the finest of proof is found in the sudden moment of one's being granted faith, (illuminating one's mind with all the convincing force of an epiphany), through the persistent reinforcement of one's reason and experience, just as it is with the man who has finally learned to trust his faithful friend, or perhaps some other individual in life, whom might likewise prove worthy of his trust.

For instance, though this trusting man know for a fact that he cannot prove to any other individual his faithful companion's trustworthiness, which he himself has come, by the test of long experience, to be assured of as a fact—although men, in an insensible manner, mockingly impugn his convictions perpetually with the sensible question, "But how do you know that this time won't be the time your 'friend' chooses to betray your trust?"—the man knows from his own objective and reasoning experience that he can rely upon the uncertain future to play out with certainty in this one regard. The simple fact is that he intimately knows his friend, just as one may come to know God, and in no different a mode than by conversing with Him—that is, by speaking to Him in prayer and by hearing from Him in alignment with His Word. And the best this man can do, the best proof he can offer, is essentially to tell others—(thus leaving the investment ultimately in their own hands)—to trust his friend as well—(prudently, of course, initially with little matters),—and to thereby steadily get to know him, if they too wish to know proof of that fellow's trustworthiness.

If clarity in this matter still remains somewhat elusive, let us take momentary heed of the following example: should a man—(whom we’ll use in meager comparison to God and His offer of salvation)—similarly tell us he can be trusted with turning 10 of our dollars into $1,000, we ultimately cannot know this to be the truth apart from entrusting that man with 10 of our dollars. Though we may look for every impersonal evidence both in favor or disfavor of his trustworthiness, satisfying whatever length of research might be available to us, which information might even then exercise over us its power of persuasion toward our deciding upon one resolution or another, still, despite all of this prudent investigation (records and hearsay being of what insufficient guarantee they are, and likewise requiring an investment of our faith), we cannot truly prove whether or not this man will do what he says he will do until we’ve for once entrusted to him that small investment which his grandiose proclamation requires from us. And so—in acknowledging our presently hypothetical and strictly-monetary offer as being completely devoid of the resonating, personal truth that fully impregnates the vastly-superior, Gospel offer,—the only sensible and likewise practical question in this scenario becomes—(if it is, indeed, proof we're seeking)—‘Does the benefit outweigh the cost, and, if so, by how much?’ or ‘What exactly do we risk losing in light of what we stand to gain?’ Verily, before Almighty God and the unparalleled gift He extends man through Christ Jesus, every man has absolutely nothing of worth to lose in trusting his Maker to prove His promised trustworthiness, but rather he has everything of worth to gain. Notwithstanding, man does stand to lose everything he cherishes for passing up, or spurning, as is more often the case, the benevolent and altruistic offer which his God extends him for his limited lifetime.

Perhaps the simple reality has been taken for granted that no one, of course, knows their friend,—or any man for that matter,—merely by looking at that individual, merely by seeing him with their physical eyes; neither can they come to ‘believe in’ this person whom they undoubtedly see—(which illustration carries the truer import of the familiar phrase 'belief in God')—strictly by the sight of him; but rather by hearing or reading and so retaining that person's spoken or written words, and observing how those words line up with that man's performances, until, if such a man be honorable and his words ring continuously true, he may come simply to be taken at his word, and be no longer viewed with suspicion. This same reality goes for God, as well—and that by His own ordination. Thus, as we have altogether reasoned out, we find that this alone can be the only ‘proof’, as the atheist means it, of God, just like God says of it in His Word,—Faith: the final step taken by one's sincere reasoning endeavors, which invested act further rewards one's understanding tenfold; and so, from this, the reasoning skeptic should have his first, albeit meager, evidence of God, if he understands nothing more. After-all, as we are told, the Lord is "a rewarder of those who diligently seek Him" - Hebrews 11:6.

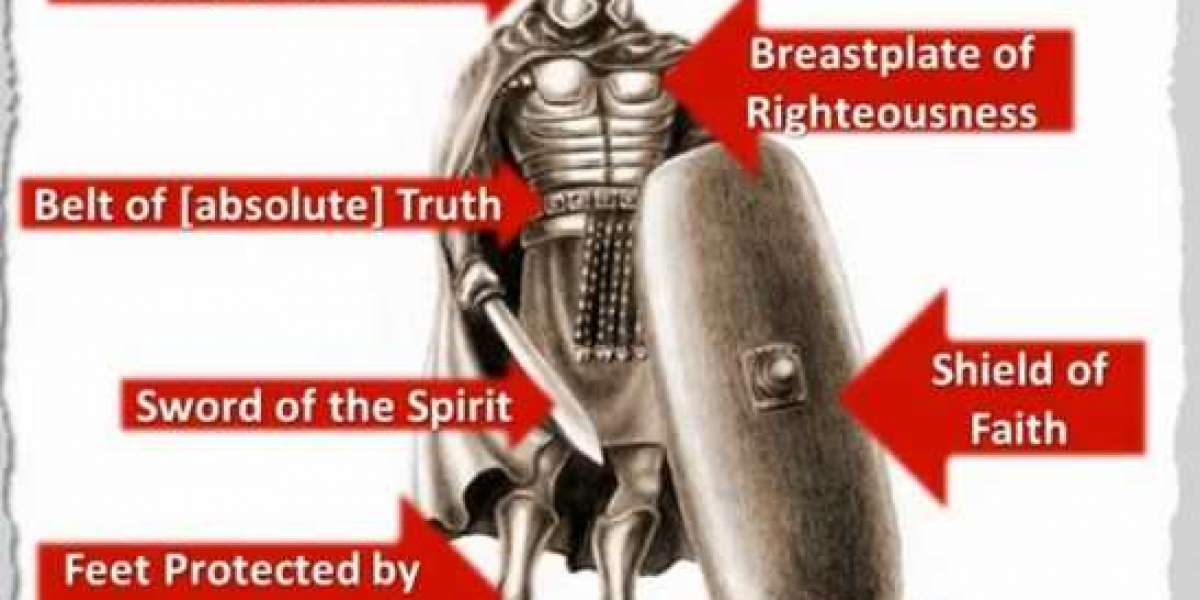

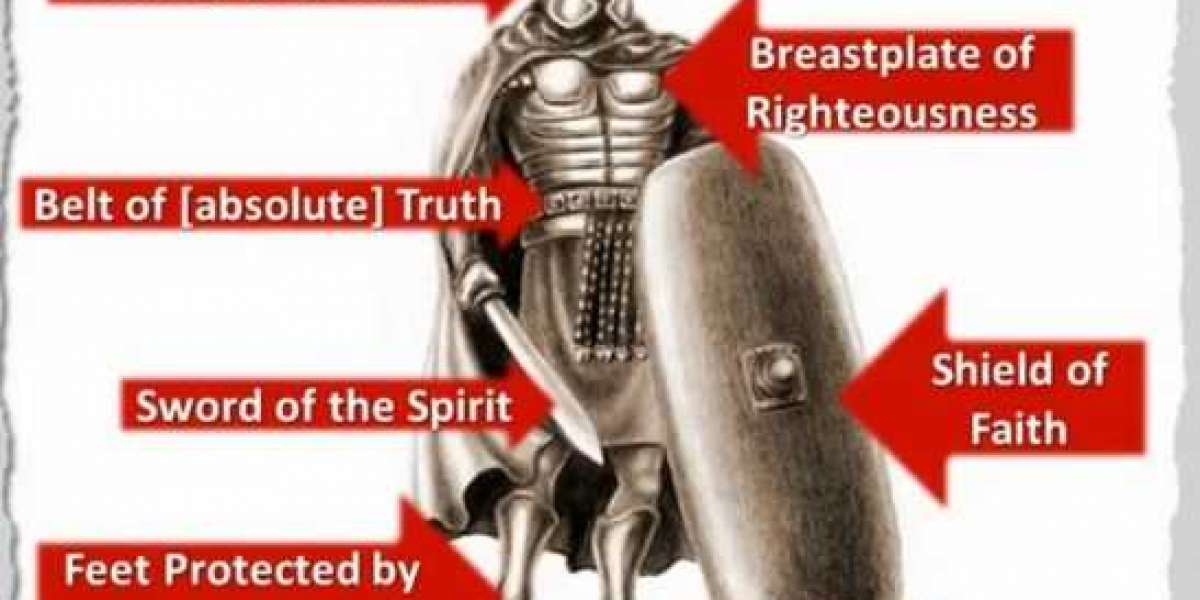

Quite reasonably, Faith in God—which is synonymous with ‘proof of God’—comes from hearing, and hearing from the Word of God, (Romans 10:17), that is to say, from what Christ testifies of Himself. Without faith, after-all, as He has told us, it is impossible to please Him, just as we'd find it the case with anybody else we'd hope to closely befriend.

"Now faith is the SUBSTANCE of things hoped for, the EVIDENCE of things not seen" (Hebrews 11:1); and, all physical things being but the shadow He casts into the world, truly "the substance is of Christ" (Colossians 2:16-17), Who Himself is "The Truth" (John 14:6), which our very hearts and consciences confirm upon the hearing.

Stavros 6 years ago

The desire to believe is an inward operation of man's will. But also the desire to reject evidence is also an inward operation of man's will. So, it is not a case of external and internal conflict of evidence of God, but conflict of internal will of acceptance or rejection.

There is a certain tool/compass that may reveal as an error. When a truth is reversible, we may suspect a logical error.

I am referring to the old story of the lawyer and his student. The student asked the lawyer to teach him the art of winning in court. Their agreement was that the student would pay the teacher after winning his first trial. Years passed, the student graduated and said to the lawyer, "Dear teacher, I'm not going to pay you because the most you can do, is to take me to court for violating our agreement. Then, if I lose the case, I should not pay you, because by our agreement I would not have won my first trial. If on the other hand I win the case, then I will not pay you respecting the decision of the judge."

The clever lawyer reversed the argument and said, "My dear student, you are going to pay me either way. Because if you win that court, you will have won your first case and you should pay me by our agreement. If on the other hand you lose that case, you will pay me by respecting the decision of the judge."

The logical error in this case is the introduction of one more element in the syllogism, that is the decision of the judge. An element that was not included in the initial agreement. By this example, I conclude that whenever an argument is reversible, it hides an error somewhere in the proof.

Another notorious error is an antinomy. The sentence, "this truth is false" has such this contraction, and it can mean anything. It is the equivalent of the Mobius loop, the snake that eats itself. It is an error by self-reference. And as such, any edifice that relies on such an antinomy, be it a whole library of books, all philosophy systems, is wrong.

In general, it is not good to try to provide proof for the existence of God. That would mean our outsmarting of God. As long as God does not wish to manifest Himself in physical plausible ways, He would not also endorse us for doing so.